I’ve been using python as the primary programming language for all of my classes, from middle to high school. However, with a variety of different machines and operating systems–macs, PC’s, OSX, Windows, ChromeOS–it has been bit of a pain getting everyone up and running and on the same page. It has been especially problematic because I like to use NumPy and, especially, the VPython module because of its nice, easy 3d visualizations.

I’ve tried Anaconda, which works great on some machines but not so much on others. One student with a Mac had to restart the kernel every time he ran a program with vpython, while others had trouble getting it to work properly at all. I do like the way it allows you to put everything into a single Jupyter Notebook, which works nicely for teaching-length programming assignments, but becomes cumbersome for longer projects. Joel Grus goes into detail about why he does not like Notebooks for teaching; much of which I agree with. I do like the Spyder IDE a lot, but I’ve run into some computers that have problems with it (constant crashes).

So, I’ve been using Glowscript a lot with the lower grades. It’s online, so you only need a browser, and its made for vpython, so you can do a lot of the numerical work with it. However, because it’s online you can’t, understandably, get it to write output files to your computer–you have to copy and paste from its output. I’m also not sure how to import user-created modules, which further limits its utility for higher-level classes.

I’ve recently run into repl.it, and I’m having a student try it out in my Numerical Methods class. It looks quite promising as it seems to be able to manage files well and we’ve tried some basic numerical programs using numpy and matplotlib. However, I’ve not got it running vPython yet (although it’s come close).

(repl.it update): One of our other teachers has been trying repl.it with the middle school class and really likes it.

I’ve also recently discovered MakeCode. I’m looking into it for the lower grades, down to 6th grade or even earlier, because it lets you write programs for Minecraft, which is very popular with a remarkably broad age group. It lets you work in blocks, python, or JavaScript. From my poking around, the first couple of things it teaches you to do in Minecraft are write statements (to generate a chicken) and the loops (to generate a lot of chickens). I’ve asked one of my 9th grade, Minecraft players to investigate, so I should have some results to report soon.

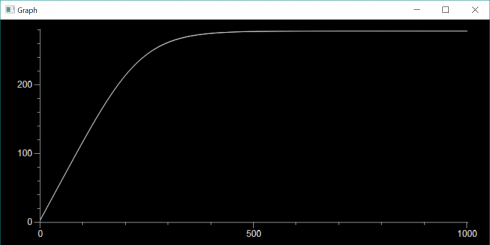

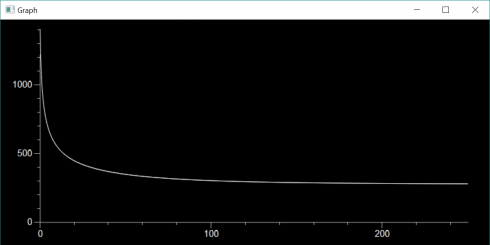

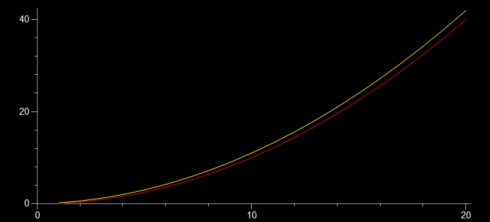

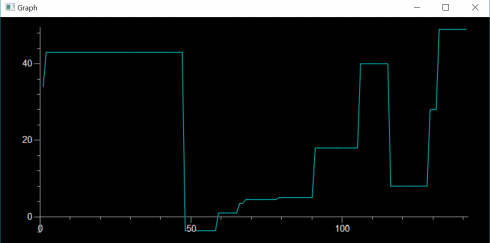

At the moment, for my most advanced class, we’re taking a whatever-works approach. We’re learning about finite differences and using matplotlib to graph the output. I have one student, mentioned above, using repl.it, and another one using Jupyter Notebook on a Mac. A different Mac user is invoking IDLE from the command line because they prefer the IDLE IDE, but couldn’t get numpy to install properly with the python 3.9 version they’d installed earlier–the command-line IDLE actually goes to their Anaconda installation. I have one student, on a Windows machine, for whom everything just works and are using their regular IDLE installation. We spent the entire class period getting everyone up and running with something, but at least now everyone has at least one environment they can use. I’m curious to see what the kids who have multiple options are going to go with.