“We want to put chemicals on it and see what happens,” she said.

I was not quite sure how to respond. First of all, I didn’t know what “it” was. Secondly, I had no idea about what chemicals the three of them wanted to “put on it”. And thirdly, I was wondering why they even thought that students could just wander into the chemistry lab and get my permission to “put chemicals” on some random stuff, just to see what would happen.

For the last question, alas, I’m afraid to say that they may, perhaps, know me too well. However, given my visceral antipathy to inexact language — especially in a science lab where safety is always a concern — based on the first two questions, they don’t know me quite well enough.

An interrogation ensued.

“It” turned out to be two sad-looking pieces of dried apple. They weren’t dried when they’d been left in someone’s locker who knows how long ago, but they were pretty dessicated now.

The “chemicals”, on the other hand, they weren’t quite so sure about. Or at least they didn’t want to tell me right away. They may have had different ideas about what they wanted to see.

“We want to see it burn and smoke!” explained the second one happily. I didn’t have to express either skepticism or approbation verbally, my face responded automatically.

“We just want to see bubbles and stuff,” suggested the first one somewhat tentatively; eying my facial expression carefully.

The third one said nothing, but she tends to reticence. I looked at her inquiringly to give me a second to think.

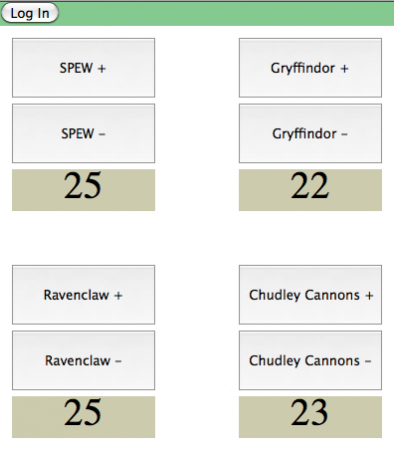

That’s when I realized that they were all in chemistry together. They’ve been working with chemicals, studying different types of reactions for the last eight months, so they probably had at least some idea about what they were asking about.

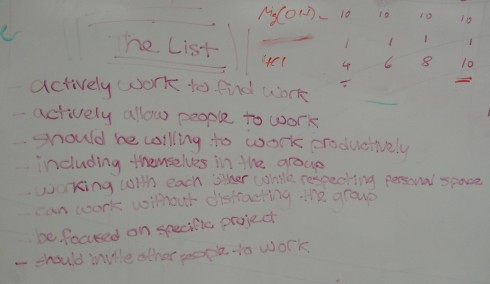

The Montessori axiom is to follow the child, and here they were expressing an interest in chemistry. It was an ill-formed interest perhaps, but an interest non-the-less, so maybe there was something I could work with.

I needed a way to gauge just how serious they were about their project, and, at the same time, tie it back to what they’d been learning in class. Were they interested enough to puts some serious thought into it?

So I told them that, if they could tell me exactly what chemicals they wanted to use, and write the chemical equations to show what would happen, I’d let them do it.

They were on it.

The first thing was to figure out what was in the apples that could react. Well, the apples had come pre-sliced, and fresh in one of those small, clear, plastic bags. The first student, who was taking charge of the group, ducked out of the room to retrieve it from the garbage can across the hall.

I’d expected that the ingredient list to be very sparse. Ideally just the single word, “apples”, with maybe the type of apple listed if the packet labelers were feeling verbose. However, it turns out that those “fresh” slices needed something to keep them looking good and tasty. So these fresh apple slices appear to contain some amount of calcium carbonate. That was a chemical they knew.

Their first thought was a single replacement reaction. If they added potassium to it then the potassium would replace the calcium and they’d see something interesting. It took a few minutes, and a little nudging of the quiet one to help out with the charges, but eventually they wrote out and balanced the reaction:

2 K + CaCO3 –> K2CO3 + Ca

The problem is, I pointed out, there’s nothing in that reaction that would produce bubbles. I didn’t even want to bring up heat and the exothermic and endothermic reactions, nor the fact that potassium is a solid, as is the calcium carbonate, which would make getting them to react dramatically a little bit difficult. I didn’t even point out what would happen if the potassium came in contact with water (or even sodium), because I know Ms. Wilson is planning on doing that little demonstration in the near future.

So what reactions produce bubbles? This took some further thought. With a few dropped hints, they came up with acid-base reactions, particularly, the reaction between calcium carbonate and hydrochloric acid. I pretty much told them what the products would be, and, with a little more coaxing of the quiet one for help, they were able to balance the reaction.

CaCO3 + 2HCl–> CaCl2 + CO2 + H2O

Now they were finally good to go. Unfortunately, it was also time to go P.E.. And they’d managed to drop one of the apple pieces into a bucket of water that my calculus students had left lying around after their bottle draining experiment.

So I told them they could try it tomorrow. Unfortunately, tomorrow is the field trip, so they’ll have to do it the day after.

We’ll see how it goes.