Today we reconstituted our small groups for science. One student was late getting their name into the bowl so did not get randomly assigned to a group, so I deviated a little from our standard procedure and asked him which group he thought would be the best for him. Not which group he most wanted to be in, but which group he could be most effective — and learn the most — in. But, as a means of following up on all of our discussion at Heifer about what makes a community, before I gave him the chance to answer I asked the entire class to identify what qualities they thought they brought to their groups, and then, separately, I asked them what qualities the would like their teammates to have.

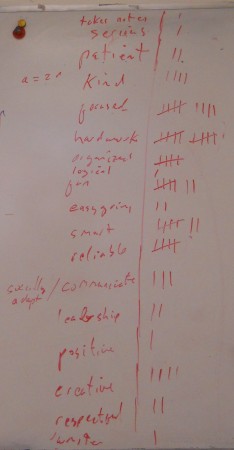

I got a number of interesting answers to the question about what they thought their qualities were. I know how hard it is to self-assess sometimes so I required that they could only put positive qualities, and allowed them to ask their peers for an external perspective.

My favorite response was from one girl who asked her friend sitting next to her what her positive qualities were, and the friend responded, “bossiness”. She thought about that for a second, then nodded and said, “that sounds about right.” When I asked them both why they thought “bossiness” was a positive quality they explained that the one girl was good at taking charge when necessary, and telling everyone what to do. I couldn’t argue with that description, because I’d observed it in their previous group work. The key part though was the “when necessary”, because while she does take charge, she’s very good at managing her group: giving everyone the opportunity for input while still being decisive. Instead of bossiness, I’d probably have used the term “leadership”.

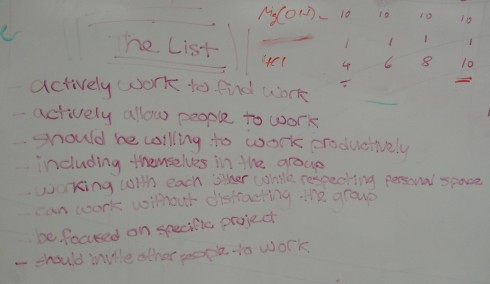

After they had the time to compile their list of qualities they wanted to see in teammates, we compiled a list on the whiteboard (see Figure 1). Perhaps it’s just that they know what I want to hear, but it was quite nice to see that the top two characteristics were:

- focused, and

- hardworking.

“Smart” and “fun” were the next most popular on the list, but after some discussion I/we decided to drop the “smart” since their criteria for smart was just having a basic level of intellectual competence, and it was somewhat less important than the other major qualities listed.

Of the remaining three major qualities that they’d like to see in teammates — focused, hardworking, and fun — I asked them each to pick the one they were going to focus on developing over the next month of group work. I asked a couple of the students who chose “fun” to reconsider since it was already one of their current areas of strength.

I then let them pick a second quality to work on from the full list, and had them write their two chosen qualities down somewhere prominent, because we’ll be checking in with them regularly over the course of the next month to see what specific things they’re doing to work on them, and how their efforts are going.

Then I let the student choose his group.

The discussion took the entire class period, and we did not get much “science” done, but if it can get students to be a bit more focused on their work it would be well worth the time.