The innate will to learn is the basic premise of the Montessori philosophy. So we emphasize giving students the freedom to explore the Montessori works, and allow them the time an space to teach each other, rather than intervening all the time. I know I find it hard to shut up sometimes and let them make the obvious mistakes, but they learn so much better that way.

Sugata Mitra wondered what would happen if you gave a computer to bunch of developing-world kids and let them use it as they would. As with Montessori, it turns out that the kids learn a lot, especially because they end up teaching each other.

Mitra’s TED talk is quite interesting in that it’s amazing just how much students will learn from a computer, even if unmediated by a teacher, if you just let them at it. Based on this work, he wants to add more computers and more unmediated spaces, all around the world. I think it’s a good idea.

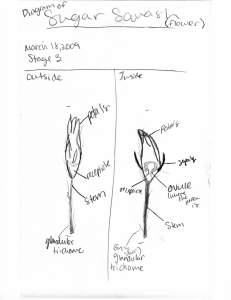

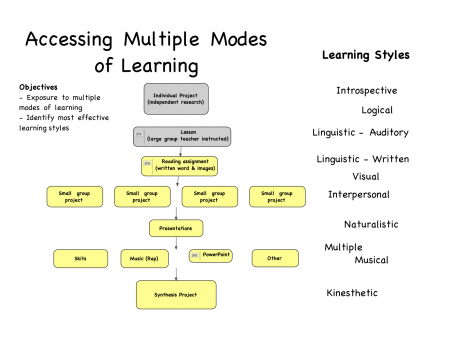

In middle school we don’t have all the Montessori works students use in pre-Kindergarten through Upper Elementary. Students and their studies are getting more abstract. Instead, there are lots of individual and group projects. I like to view it as a set of apprenticeships: learn to be a scientist, learn to be an author, learn to be a geographer, and so on. One of the key questions I juggle is how “real” should their projects be. Should I give them a basic assignment and have them figure out the questions on their own, or should I point them toward specific resources, like chapters in the textbook. The answer is somewhere in between, but there is a constant tension. I also just try to mix it up a bit.

At any rate, Mitra’s work is interesting and I think its long-term results will probably affect the way we teach Montessori middle schools.