90% of the cells in your body are bacteria and other provocative facts about the Domain Bacteria are the subject of a great but long article by Valarie Brown.

[R]esearchers have also discovered unique populations adapted to the inside of the elbow and the back of the knee. Even the left and right hands have their own distinct biota, and the microbiomes of men and women differ. The import of this distribution of microorganisms is unclear, but its existence reinforces the notion that humans should start thinking of themselves as ecosystems, rather than discrete individuals.

—Brown (2010), in Miller-McCune.

The article makes for great reading during this cycle’s work on classification systems and evolution. One choice paragraph summarizes the fundamental differences between the domains of life:

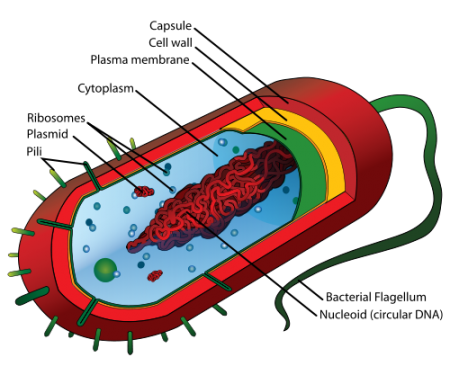

There’s such ferment afoot in microbiology today that even the classification of the primary domains of life and the relationships among those domains are subjects of disagreement. For the purposes of this article, we’ll focus on the fundamental difference between two major types of life-forms: those that have a cell wall but few or no internal subdivisions, and those that possess cells containing a nucleus, mitochondria, chloroplasts and other smaller substructures, or organelles. The former life-forms — often termed prokaryotes — include bacteria and the most ancient of Earth’s life-forms, the archaea. (Until the 1970s, archaea and bacteria were classed together, but the chemistry of archaean cell walls and other features are quite different from bacteria, enabling them to live in extreme environments such as Yellowstone’s mud pots and hyperacidic mine tailings.) Everything but archaea and bacteria, from plants and animals to fungi and malaria parasites, is classified as a eukaryote.

—Brown (2010).

Brown also gets into a discussion of if bacteria think:

[B]acteria that have antibiotic-resistance genes advertise the fact, attracting other bacteria shopping for those genes; the latter then emit pheromones to signal their willingness to close the deal. These phenomena, Herbert Levine’s group argues, reveal a capacity for language long considered unique to humans.

—Brown (2010).

Trimming this article down would probably make it a good source reading for a Socratic Dialogue.

Bacteria are the sine qua non for life, and the architects of the complexity humans claim for a throne. The grand story of human exceptionalism — the idea that humans are separate from and superior to everything else in the biosphere — has taken a terminal blow from the new knowledge about bacteria. Whether humanity decides to sanctify them in some way or merely admire them and learn what they’re really doing, there’s no going back.

—Brown (2010).