I’ve always been in favor of alternate means of presenting information, especially for recipes.

Stop-Motion Biscuit Cake from Alan Travers on Vimeo.

(via The Dish)

Middle and High School … from a Montessori Point of View

I’ve always been in favor of alternate means of presenting information, especially for recipes.

Stop-Motion Biscuit Cake from Alan Travers on Vimeo.

(via The Dish)

Brian Cox explains (on the BBC) explains how electron shells are like standing waves, and how that relates to the sizes of atoms, and explains why atoms are mostly space.

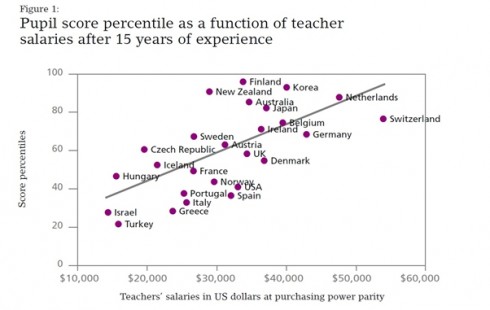

Teachers are, I believe, human too. So it should not be surprising that more motivated teachers perform better. Oscar Marcenaro-Gutierrez and Peter Dolton highlight an OECD report that shows the benefits of increasing teacher pay.

What’s most interesting though is their explanation of the data. It’s not necessarily that if you pay an individual teacher more they work that much harder, but that if you pay more you increase the status of the profession and so you attract more potential teachers and are able to select better teachers:

… improving teachers’ pay improves their standing in a country’s income distribution and hence the national status of teaching as a profession. As a result of this higher status, more young people will want to become teachers. This in turn makes teaching a more selective profession and hence facilitates the recruitment of more able individuals.

Higher status and higher pay are invariably linked but the two can provide separate driving forces to engineer better recruits to the profession. The key hypothesis is that better pay for teachers will attract higher quality graduates into the profession and that this will improve pupil performance.

— Dalton and Marcenaro-Gutierrez (2011): If you pay peanuts, do you get monkeys? in CenterPiece Magazine

(via The Dish).

So the actual pay is secondary to the status conferred by the job. I would further speculate that teachers motivated more by status rather than pay are more likely to want to excel at their work, since the quality of their work is tied more on their self-worth.

Last fall, the Good Shepherd Lutheran Church had a pumpkin patch with a trebuchet. They launched a few pumpkins for the kids.

Their design was simple — not for competition, but something I’d like my students to emulate sometime.

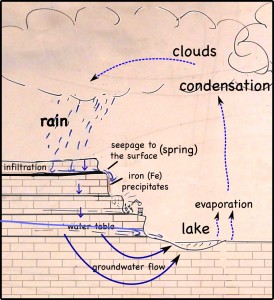

Although it was high in sulfur, the quarry company mined the thin coal seam that cut across the limestone quarry/landfill.

The layer of coal is pretty impervious to water, so it blocks vertical infiltration of water, which forces the water to the surface as springs.

At the surface, when the water is exposed to oxygen in the atmosphere, dissolved iron precipitates to produce a red mineral that stains the quarry walls.

The iron gets into the water when pyrite crystals (FeS2) in the coal dissolves. While the iron precipitates, the sulfur remains in the water, making it more acidic. Dealing with the acid can be a huge problem in large coal and metal mines.

Not all the pyrite is dissolved however, and since this particular coal seam has a lot of pyrite, it is not economical to burn since the burnt sulfur (as sulfur dioxide gas) would have to be captured — otherwise it produces acid rain.

Although we’re not precisely sure why, the choir was quite the popular choice this year. The students are enthusiastic, and our music teacher, Mr. E., does an awesome job. It’s really nice to run into them practicing in the commons.

In this case they were in the Keeping Room — long, vaulted ceiling, remarkable acoustics. They practiced at one end; people accumulated at the other.

[Sarcasm] appears to stimulate complex thinking and to attenuate the otherwise negative effects of anger

— Miron-Spektor et al., 2011. Others’ anger makes people work harder not smarter: The effect of observing anger and sarcasm on creative and analytic thinking. in J. Applied Psychology via Smithsonian Magazine.

If there’s anyone for whom sarcasm is a primary language, it’s probably adolescents. It can be used to bully or put down, but, according to Richard Chin (2011), is more often used among friends; a bit like positive aspects of teasing.

Chin has a good article that looks over recent research into how sarcasm works on Smithsonian.com.

Apparently, sarcasm exercises the brain more than regular comments:

… observing anger communicated through sarcasm enhances complex thinking and solving of creative problems”