A recent article by Diane Halpern in Science looks at the data about single-sex schooling and finds little evidence of benefits.

There’s a podcast interview with Halpern that elaborates on the story, but Tamar Lewin’s article in the New York Times does a great job at looking at the different sides of the issue.

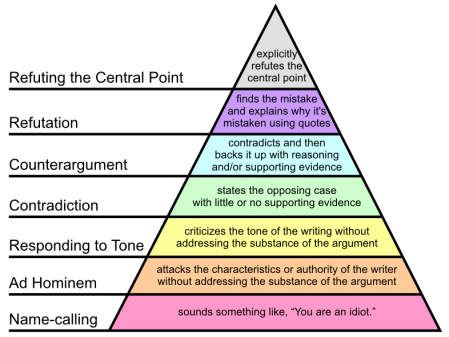

… sex-segregated education—is deeply misguided, and often justified by weak, cherry-picked, or misconstrued scientific claims rather than by valid scientific evidence. There is no well-designed research showing that single-sex (SS) education improves students’ academic performance, but there is evidence that sex segregation increases gender stereotyping and legitimizes institutional sexism.

— Halpern et al., 2011: The Pseudoscience of Single-Sex Schooling

My personal, (very) anecdotal experience would argue the opposite, however. At least in secondary school, not having all the inter-gender interactions was quite beneficial. It may not have made me the best student (or even a good student), but it was at least one less complication to worry about while I was trying, or trying to avoid, learning.

The author are directors of the American Council for CoEducational Schooling, so they do have a definite point of view. Their Why Co-Ed? page makes the arguments for Co-Ed schools in nice bullet points.

Their arguments seem to be based on the evidence that gender segregated schools encourage stereotyping, usually to the detriment of the girls. Gender segregation is particularly suspect when it’s based on the idea that boys and girls learn very differently. There are certainly differences (e.g. as in their approach to games, and blogging) but having all this diversity in approaches and perspectives in the same classroom has been generally beneficial in my experience.

My only real major outstanding question is the effect of the increased sex drive that comes with puberty on students’ ability to learn. Although they admit it as a potential problem, their counter is that students in single-sex environments don’t learn how to interact properly with the other gender. Adolescents need all the opportunity they can get to learn how to normalize their interactions with the opposite gender. My own anecdotal evidence would definitely support this contention, but I’d like to see it backed up with more research, nonetheless.

… the rise in testosterone at puberty, which happens in both boys and girls, has one clear-cut effect: elevating sex drive in both males and females. There is no question that this can change the dynamics in a middle- or high-school classroom;

…

… there is evidence that gender segregation disturbs boy-girl interactions when the two sexes do come together at lunch, recess, or more formal social gatherings.2 Lacking the opportunity to work together in a serious, non-sexual environment, boys and girls may over-glamorize, misunderstand, and even harass the other sex when they do have a chance to mingle outside the classroom.

— Halpern et al., 2011: The Pseudoscience of Single-Sex Schooling

I’m troubled about the use of the word “may” in the second paragraph; the evidence either way seems equivocal. It’s good, though, to see someone compiling the research.

I do think single-gender education should be an option that’s available, but I’d like to see the arguments either way be based on sound science. The simple fact that boys and girls learn differently (on average) does not mean they would benefit from learning separately.