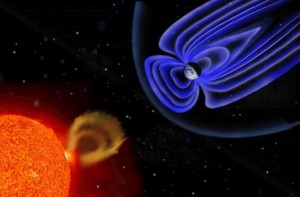

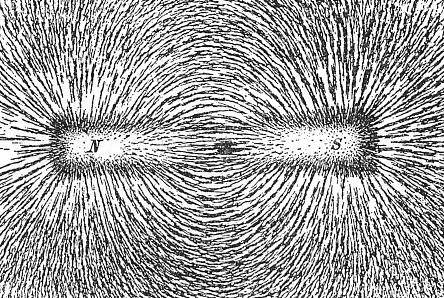

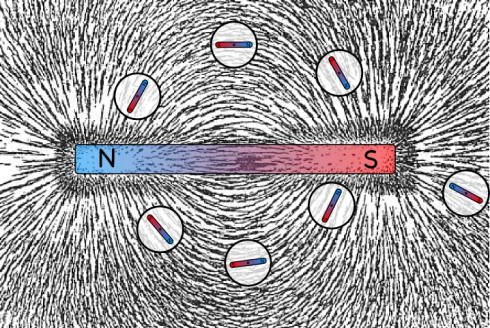

Magnetic fields and electric fields are directly related:

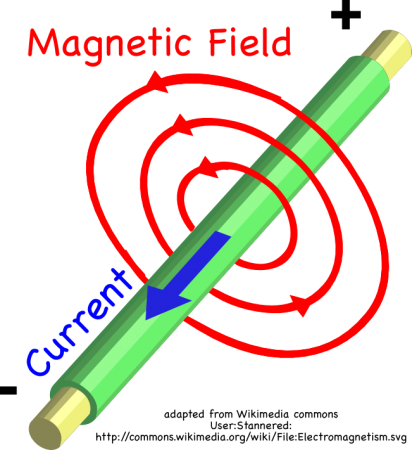

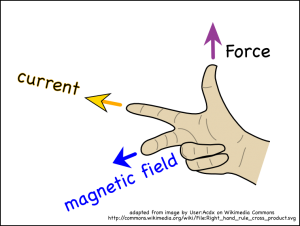

- We saw before that a current moving through a wire creates a magnetic field.*

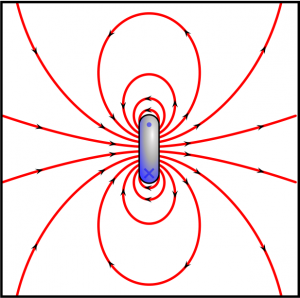

- The opposite is also true. A moving magnetic field induces an electric field (and thus a current) in a wire (from Faraday’s Law).

Electromagnetic Induction

So, simply moving a magnet next to a wire, or through a coil of wire, will induce a voltage in the wire.

You can create more voltage by:

- Faster motion.

- More coils of wire.

Notes:

Relative Motion: moving the coil of wire around the magnet would create the same voltage as moving the magnet through the coil.

Conservation of Energy: By moving the magnet, you convert the kinetic energy of the motion to electrical energy.

- So the greater the voltage you want to create, the more energy it will take to move the magnet. If you have a lot of coils and are creating a large voltage, the magnet is going to be harder to push through the coil because the induced electrical field induces a magnetic field that opposes the original magnet.

Current Direction: Moving the magnet back and forth will switch the direction of the current back and forth as well, creating an alternating current.

Faraday’s Law (37.2)

The voltage induced in a coil depends on the number of loops and the rate at which the magnetic field changes (as well as the resistance of the coil material — better conductors will permit a greater voltage).

Electrical Generators

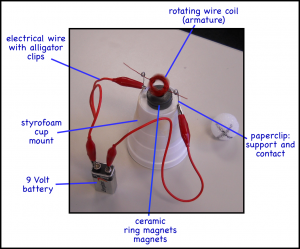

If we make a coil like the ones we used to make the motors, but took out the battery from the circuit then the motor would not move. However, if we rotated the coil ourselves, mechanically, as it sat over the magnetic field, we would create a current in the wire. This is how generators create electricity.

Generators (mostly) create electrical currents by rotating wire coils inside magnetic fields.

Alternating Current Generators

A generator adapted from our motor would only have a current as long as the copper wire from the exposed side of the coil was completing the circuit. When the insulated side was touching the paperclip there would be no current. Electrical power plants are set up so that the rotating coil (also called an armature) is always in electrical contact, but when the coil goes through the second half of its rotation the current is reversed in direction. This switching back and forth of the direction of the current in the wires is how alternating currents are created.

Power Plants

Electrical power plants turn their wire coils (armatures) in any number of ways.

- Wind turbines and hydroelectric turbines use wind and water respectively to spin their wire coils directly.

- Most other power plants produce heat energy to boil water, which creates steam, which is piped past the turbines that turn the coils.

- Coal, oil and natural gas plants burn these fossil fuels to produce the heat;

- nuclear power plants use the heat generated from radioactive decay to produce the steam that turns the turbines;

- on the other hand, solar panels don’t use turbines or any moving parts to produce electricity.

Motors versus Generators (37.4)

Motors and generators are essentially the same, except that motors use electricity to produce mechanical energy, while generators use mechanical energy to produce electricity.

Notes

* edited March 22nd, 2012 at 10:01 pm, in response to feedback in this comment.