I’ve always been in favor of alternate means of presenting information, especially for recipes.

Stop-Motion Biscuit Cake from Alan Travers on Vimeo.

(via The Dish)

Middle and High School … from a Montessori Point of View

I’ve always been in favor of alternate means of presenting information, especially for recipes.

Stop-Motion Biscuit Cake from Alan Travers on Vimeo.

(via The Dish)

I have a neat little tea strainer that sits inside my almost perfect teacup, yet I’m usually at a loss about what to do with it when I take it out of the cup. When the lid is upside down, the strainer can sit nicely into a circular inset that seem perfectly designed for it; however, if I want to use the lid to keep my tea warm — as I am wont to do — I have to move the strainer somewhere else.

One option is to just put the strainer in another cup, but then air can’t circulate around it, and instead of drying, the used tea leaves stay wet and, eventually, turn moldy. A flat saucer would be better, but not perfect.

Of course, I could just empty out the strainer, wash and dry it as soon as I’m done steeping the leaves, but there are a few ancillary considerations with respect to time that make this a sub-optimal solution.

So, since we have a kiln on campus that sees regular use, I thought I’d sit in on the Middle School art class and make my own ceramic tea strainer holder. Since I’ve also been thinking about Philip Stewart’s spiral, and de Chancourtois‘ helictical periodic tables, and been inspired by Bert Geyer’s attempts at making sonnets tangible, it eventually occurred to me that an open helictical form would work fairly well for my purposes.

I’ve cobbled together a design using Inkscape, and layered it onto a cylinder in Sketchup to see what it would look like.

So far the reactions from students has been quite diverse. I have one volunteer who’s wants to help, and I’ve sparked some discussion as to if what I’m doing actually qualifies as art. There is a lot of curiosity though. The middle-schoolers will probably be doing some type of physical representation of the periodic table, so I’m hoping this project gets them to think more broadly about what they might be able to do.

That would at least be our address if we were on the “extended” Manhattan Street Grid, according to this website.

Just goes to show that everything is relative.

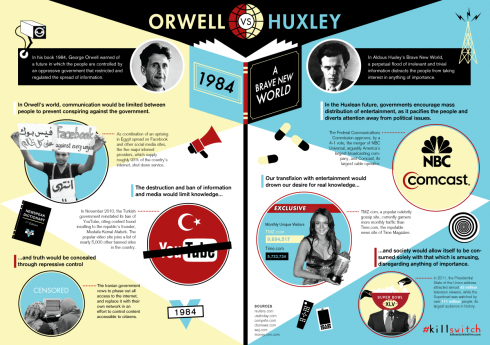

World-shaker tries to draw the modern parallels to 1984 and Brave New World in graphic form.

Orwell’s (1948) distopian view of the future in 1984, warned against the government developing the ability to exert constant, repressive monitoring of everyone, controlling the means of communication and, perhaps more importantly, the use of language. Huxley’s (1932) Brave New World, on the other hand, saw a mass media using your apparent predilection for trivialities to distract you from the important things. These two books are staples of secondary school literature, and it’s easy to see modern parallels; “kinetic military action” is currently my favorite Orwellian term.

Unfortunately, drawing modern parallels to historic literature is fraught with difficulty because it’s so easy: the human brain is predisposed to seeing patterns. World-shaker’s attempt is interesting, but flawed. One of his commenter points out that he compares the entertainment website TMZ to Time.com’s news site, which only gets half as many visitors. However, the New York Times’ site gets three times as many visits as TMZ so perhaps he’s fudging the statistics a little to show the trend toward frivolous media.

There are other examples, but the graphic makes does provide a basis for an interesting conversation. The most interesting aspect is that it shows the U.S.A trending more toward Huxley, while repressive Middle-Eastern regimes seem to be trying to make Orwell’s vision more of a reality.

While I do like to use animated gifs, these apparent animations are actually still images that, because of the arrangement of colors and shapes, your brain interprets as moving. Akiyoshi Kitaoka has an extensive gallery. It comes with the warning though: ‘works of “anomalous motion illusion”, … might make sensitive observers dizzy or sick.’ (Kitaoka, 2011).

We watched Stanley Kubric’s, Dr. Strangelove, today as part of our mini film festival. Most of the middle and high school students got the choice of what to watch, but the Dr. Strangelove was required for the American History students.

My second question during our discussion after the movie was, “What does this have to do with the Cold War?” I got a number of blank stares. The next question was, “Do you know what the Cold War was?” Apparently they’ll be getting to that next semester.

Dr. H tells me that she’s heard the complaint from the college history department that incoming students don’t know much, if anything, about the Cold War. It’s now history. It occurred before any of them were born. Is this a lament? An observation about aging? I’m not sure.

There’s a place on the road to school where you crest a little rise and the St. Albans golf course opens up before you. “Zen-like,” I’ve heard it described. On one lovely fall morning last week the view was absolutely ridiculous. I had to stop.

Resisting the coming winter, warmer air from down south just pushed over the hills overnight, trapping the cooler air in the valley, creating a thermal inversion that trapped a layer of fog just below the tops of the hills. Small tendrils of mist were rising off lake in the bottom of the valley, feeding the fog layer as the cooler valley air condensed the water vapor evaporating off the still warm lake.

Combine the fog, mists, early morning sunlight just beginning to reach into the valley, and the brilliant fall colors contrasting against the still-green lawns, and the result was absolutely amazing.

“It’s one of the places I’m most proud to bring people when they visit St. Louis,” commented (more or less) one of the other faculty on our field trip to the Laumeier Sculpture Park. My hope was that this trip, combined with our visit to the Leonardo Da Vinci Exhibition, would be a nice way to demonstrate that the distance between art and science isn’t so large after all.

I required all of my students (physics and middle school science) to identify their favorite piece and sketch it. We’ll be covering forces, balance and mechanics in the coming quarter, making this part of the spark-the-imagination part of the lesson.

Also, detailed sketches are not easy. An accurate drawing requires a lot more careful observation than even taking a picture. By trying it themselves they’d get a much greater appreciation of Da Vinci.

The large pieces are quite impressive. The brightly painted metal tank combination at the top of this post just towers over everything. However, one of the neatest was carved out of one enormous piece of wood. It’s made to emulate the distinctive, ridged bark of the cottonwood tree. The artist accentuates the ridges and valleys quite elegantly, making a wonderfully warm and organic abstraction.

There’s also an indoor museum (which was closed while we were there), and, apparently, pieces are added and taken away so the park is worth revisiting. The only problem is that you’re not allowed to climb on the sculptures. This is a quite understandable precaution to protect the pieces, but, as some of the students observed, the sculptures “invite” you into and onto them. It’s a stark contrast to the St. Louis City Muesum, which is designed specifically to be played on.