From our Eminence Immersion.

Middle and High School … from a Montessori Point of View

A discussion of the physics of flight, interspersed with birds of prey swooping just centimeters from the tops of your head, made for a captivating presentation on avian aerodynamics by the people at the World Bird Sanctuary that’s just west of St. Louis.

The presentation started with the forces involved in flight (thrust, lift, drag and gravity). In particular, they focused on lift, talking about the shape of the wings and how airfoils work: the air moves faster over the top of the wind, reducing the air pressure at the top, generating lift.

Then we had a demonstration of wings in flight.

We met a kestrel, one of the fastest birds, and one of the few birds of prey that can hover.

Next was a barn owl. They’re getting pretty rare in the mid-continent because we’re losing all the barns.

Interestingly, barn owls’ excellent night vision comes from very good optics of their eyes, but does not extend into the infrared wavelenghts.

Finally, we met a vulture, and learned: why they have no feathers on their heads (internal organs, like hearts and livers, are tasty); about their ability to projectile vomit (for defense); and their use of thermal convection for flying.

The Sanctuary does a great presentation, that really worth the visit.

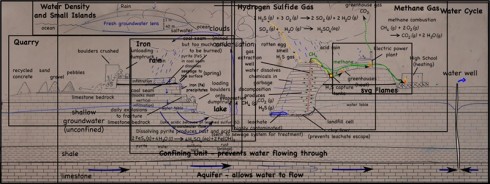

Although it was high in sulfur, the quarry company mined the thin coal seam that cut across the limestone quarry/landfill.

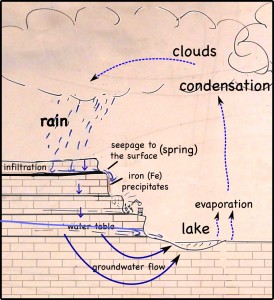

The layer of coal is pretty impervious to water, so it blocks vertical infiltration of water, which forces the water to the surface as springs.

At the surface, when the water is exposed to oxygen in the atmosphere, dissolved iron precipitates to produce a red mineral that stains the quarry walls.

The iron gets into the water when pyrite crystals (FeS2) in the coal dissolves. While the iron precipitates, the sulfur remains in the water, making it more acidic. Dealing with the acid can be a huge problem in large coal and metal mines.

Not all the pyrite is dissolved however, and since this particular coal seam has a lot of pyrite, it is not economical to burn since the burnt sulfur (as sulfur dioxide gas) would have to be captured — otherwise it produces acid rain.

A single, half-day, visit to the landfill and quarry brought up quite the variety of topics, ranging from the quarry itself, to the reason for the red colors of the cliff walls, to the uses of the gases that come out of the landfill. I still have not gotten to the details about the landfill itself, but I’ve put together a page that links all my posts about the quarry and landfill so far.

There was so much information that we spent the better part of the following week debriefing it in the middle-school science class.

The map below gives a good aerial view of the site.

View Landfill and Quarry (as of 11/26/2011) in a larger map

Almost a thousand years ago, 20,000 people lived at a place called Cahokia. At the center of their city, was the largest artificial mound in North America. A large part of Cahokia’s success is surely its location: near the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers — just across the Mississippi from modern-day St. Louis. Yet less than 400 years later (see timeline) the city was abandoned, and no one is quite sure what happened.

Our middle and high school took a trip out to Cahokia last month. It was during the same intercession between quarters when we visited the Laumeier Sculpture Park, the Da Vinci Exhibition, and did our brief biological survey of the campus.

The elevation of the main mound, sitting on the flat Mississippi flood plain, with the St. Louis skyline in the distance, was a great place to talk about the importance of physical geography in the location of cities (your biggest cities are always going to be on rivers, or the ocean or, often, both) and to reflect on how history repeats itself — a once thriving metropolis is nothing now but displaced piles of alluvium and mystery.

View Cahokia in a larger map

Cahokia is a World Heritage Site, and it has an excellent museum. I particularly liked the detail in their life-sized reconstruction of a section of the city.

Their website is also good. Apart from the timeline, mentioned above, they have a nice interactive map for details about each of the numerous mounds, and a long page about the archeology.

The site is pretty big, so you can spend a fair amount of time exploring. Fall, when the leaves have turned color, and the air has cooled a little, is an excellent time to visit.

“It’s one of the places I’m most proud to bring people when they visit St. Louis,” commented (more or less) one of the other faculty on our field trip to the Laumeier Sculpture Park. My hope was that this trip, combined with our visit to the Leonardo Da Vinci Exhibition, would be a nice way to demonstrate that the distance between art and science isn’t so large after all.

I required all of my students (physics and middle school science) to identify their favorite piece and sketch it. We’ll be covering forces, balance and mechanics in the coming quarter, making this part of the spark-the-imagination part of the lesson.

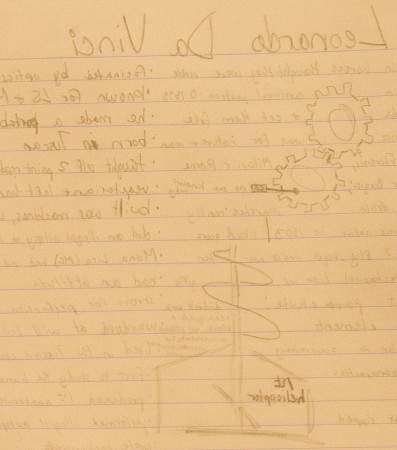

Also, detailed sketches are not easy. An accurate drawing requires a lot more careful observation than even taking a picture. By trying it themselves they’d get a much greater appreciation of Da Vinci.

The large pieces are quite impressive. The brightly painted metal tank combination at the top of this post just towers over everything. However, one of the neatest was carved out of one enormous piece of wood. It’s made to emulate the distinctive, ridged bark of the cottonwood tree. The artist accentuates the ridges and valleys quite elegantly, making a wonderfully warm and organic abstraction.

There’s also an indoor museum (which was closed while we were there), and, apparently, pieces are added and taken away so the park is worth revisiting. The only problem is that you’re not allowed to climb on the sculptures. This is a quite understandable precaution to protect the pieces, but, as some of the students observed, the sculptures “invite” you into and onto them. It’s a stark contrast to the St. Louis City Muesum, which is designed specifically to be played on.

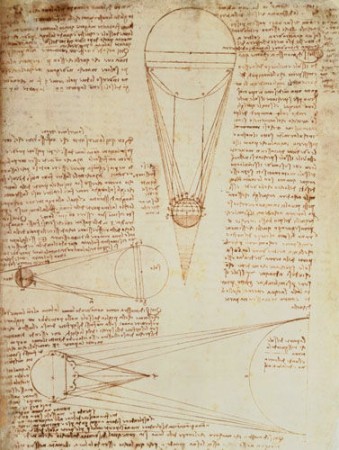

Working models of Leonardo Da Vinci’s devices, and video of his sketchbook, so inspired one student that she emulated Da Vinci’s style as she took her notes during our visit to the Da Vinci Machines Exhibition. While I’d asked them to bring their notebooks, I’d not said anything about taking notes (nor is there to be a quiz afterward) so it was very nice to see this student’s efforts. The exhibition is in St. Louis at the moment, until the end of the year.

What I liked most about the exhibit is that you can operate some of the reconstructions of flywheels, gears, pulleys, catapults, and other machines that came out of DaVinci’s notebooks.

Da Vinci did a lot with gears, inclined planes, pulleys and other combination of simple machines, so the exhibit is a nice introduction to mechanics in physics. The exhibition provides a teacher’s guide that’s useful in this regard.

It’s an excellent exhibition, especially if you spend some time playing with the machines.

Part of the afternoon chores at the Heifer Ranch was milking the goats. It was not something required of the students, but since our barn was located right next to the goats’ milking barn, a lot of them volunteered to try it out.

Most used the somewhat dainty, one handed technique, and I’ll confess I was among that group, but a few students (see first image) really got into it.

After milking, the goats’ teats are dipped in iodine solution (25 ppm recommended by McNulty et al., 1997) to kill any germs and prevent infection.

As for the green splotches on the backs of the goats. On our first morning at the Heifer Ranch we had walked past a paddock with about half a dozen goats. A student noticed the green and asked why. Fortunately, we had a guide to explain a little about the basics of animal husbandry – apparently, the marks indicate which goats are likely to be pregnant.