One of the highlights of the Heifer Ranch trip was the chance for students to spend a night in their global village. It’s really a set of villages, each simulating a life in an under-developed part of a different developing country.

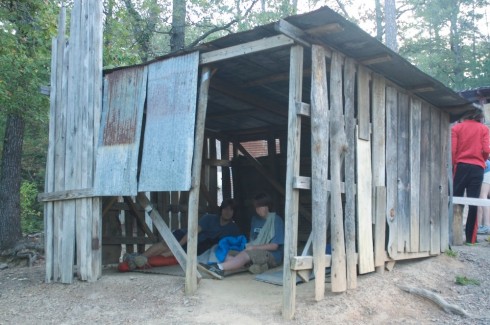

The Guatemalan house is pretty nice; it keeps you out of the elements, you have actual beds, and running water. The Thai houses are actually pretty awesome. They stand on stilts next to the open fields, giving good air circulation and elegant views. They remind me a lot of some of the older houses from where I grew up. The refugee camp, on the other hand is pretty decrepit. The slums aren’t much better but at least have one house with a wooden floor, though the door was so broken it was pretty useless.

Our students were assigned villages at random, but varying numbers were placed in each village to replicate the population densities more accurately. One adult was assigned to each village. We were supposed to act as if we were incompetent (not hard I know), either as two-year-olds or senile elders.

I ended up in the high population slums.

On the positive side, I was not the only adult there. Mrs H., who had joined our group with her daughter for the week of activities at Heifer, was also assigned to the slums. On the negative side, she and the girls commandeered the one “posh” building that had an actual floor to sleep on. The boys and I had to sleep on the hard, stony ground.

It didn’t help that one of the boys was “pregnant”. One person in each group been given a water balloon in a sling and told to keep it with them, safe, until dinner, when they would “give birth”, at which point the others in the “family” could help take care of the “child”. A key objective was for the child to survive until morning.

The boys scouted all the houses in the village and scavenged a large piece of metal grating to sleep on. It was not great, but it was doable. Better, at least, than the concrete-hard, uneven ground.

There was a lot more that happened on that night. None of the groups was given enough to be comfortable on their own. There was a lot of haggling, trading and even commando raids, but, in the end, they pulled together and made something of it.

The experience was quite useful, I think. Conditions were uncomfortable enough to register with the students, though a single night is not enough to really internalize all the challenges of urban slums where over one billion people spend their lives. But it does provide some very useful context for the poignant images of Jonas Bendiksen (Living in the Slums) and James Mollison (Where Children Sleep).