Sarah Ellison’s excellent article in Vanity Fair about the collaboration between the Guardian newspaper and Wikileaks in publication of leaked documents, has got me thinking about how teaching needs to adapt to the internet age.

The most interesting theme in Ellison’s article is the contrast between old and new media: Julian Assange’s web-based Wikileaks and the 200-year-old British newspaper, the Guardian (which, I will confess, has a wonderful football podcast).

The conflicts between the two organizations’ cultures has apparently lead to a lot of friction and miscommunication, but also resulted in a fairly effective collaboration. The Guardian has been one of the more active newspapers in exploiting the internet, but it provides the institutional integrity and journalistic tradition that seems to be able to temper some of the manic enthusiasm of Wikileaks’ zealous idealists.

It is no surprise that Wikileaks and Wikipedia share a core precept; transparent organizations work better (of course Wikipedia has put this into practice in its own organization, while Wikileaks aims to reduce the opacity of other organizations). And it should be no surprise that Wikileaks’ model has many supporters who are digital natives. What is interesting is how much the new media needs the old media, and how a forward thinking organization, like the Guardian, can adapt to, and take advantage of, the new opportunities that come from new organizations like Wikileaks.

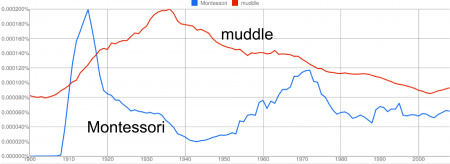

Which takes us back to education and the internet. If we can agree with Daniel Pink and myriad others (like Ken Robinson) that traditional schooling is not effective at developing students’ creativity, and that constructivist approaches like Montessori do a much better job, then the parallel with the Guardian-Wikileaks collaboration, is that programs like Montessori are ideally placed to blossom if it can take full advantage of the new, developing, technological innovations (like Saguta Mitra‘s).

Like the Guardian, Montessori needs to embrace the new techniques the internet allows, but it is essential it is done with the same care and consideration that Maria M. applied her observations of what works in teaching. The Montessori method, has almost 100 years of tradition that needs to serve as ballast in an era when many are looking for new approaches to education, and we are trying to strike the right balance between what we know works and what we hope will.