Over the winter, we read Brian Swimme’s The Hidden Heart of the Cosmos as part of the HMC Montessori Training Program. Swimme is one of those people trying to reconcile science and religion, or at least some type of spirituality.

He argues that crass commercialism, embodied by the consumer culture and a lot of television that is excrescent and dis-empowering, has replaced the spirituality that our ancestors sought in the dark, quiet reaches of the night. Then they had the time to contemplate the meaning of life and their place and even purpose in the universe. Now we try to respond to a rapidly changing world with no time to consider the fundamental questions.

I tend to be a bit skeptical about just how useful it is to examine the intersection of the sacred and the scientific. The scientific perspective is a powerful way of looking at the world. Spirituality seems to be one of those fundamental needs of human beings. I’ve never found it difficult to see the wonder in the natural world around me (which is why things like texture photography fascinate me). But when we try to describe the natural world in terms of religion and spirituality, I get a bit uncomfortable. When you’re treading the boundary between what we can observe objectively and what we feel subjectively, it’s all to easy to slip between one and the other. To stretch the scientific truth to accommodate the poetic language or metaphor. And so, it’s the little things that end up bugging me to no end.

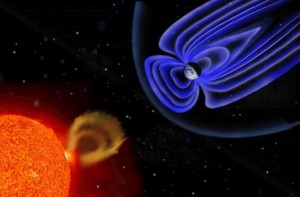

Copernicus revolutionized the way western civilization viewed the world and itself, Swimme notes. The Earth was no longer at the center of the universe. The Sun did not revolve around us, we revolved around it. So when you see the Sun going down at sunset, it’s not really going down, the Earth is turning away. Except that it is and it isn’t. If the Earth is rotating you away from the Sun, or if the Sun in going down past the horizon, is just a matter of your point of view.

If you want to describe the motion of the planets, the easiest model to construct is one where the Sun is the stationary reference point at the center of the solar system. But, if you were a glutton for punishment, you could write the equations of motion such that the you were the stationary reference point and everything else moved relative to you. It’s a bit like thinking about yourself on a boat floating down a stream. To an observer sitting on the bank you are moving downstream, but to you, the guy on the bank is moving and you’re staying in the same place.

So I get a little agitated when Swimme points out how remarkable it is to think about the fact that we occupy such a small place in such a large universe. He argues that it should broaden your perspective on the universe, and open your mind to larger questions. But I find it just as remarkable, or perhaps even a little more so, to consider the world where I am not moving, and everything else is spinning in some ridiculously complicated dance around me.

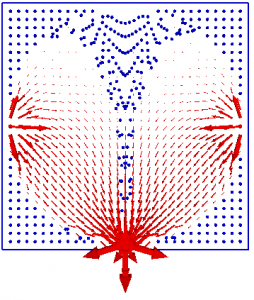

I think of Swimme at times when I’m trying to model solute transport through a fluid. Should I try to follow the motion of individual particles with the fluid. Should I take the broader view of the flow through the system. Or should I try to mix the two approaches. Either way, the math should give the same result, since I’m just trying to describe the same thing from different point of view (of course the problem is in how compatible the different approaches are to being programmed).

I know I’m missing the main point of the Hidden Heart of the Cosmos here because of my own hang-ups, so I’ll post an excellent video interview of Brian Swimme by Bob Wright, the author of Nonzero, so he can better explain himself. (If you can’t get the video to play, you can read the transcript.)