That would at least be our address if we were on the “extended” Manhattan Street Grid, according to this website.

Just goes to show that everything is relative.

Middle and High School … from a Montessori Point of View

That would at least be our address if we were on the “extended” Manhattan Street Grid, according to this website.

Just goes to show that everything is relative.

While I do like to use animated gifs, these apparent animations are actually still images that, because of the arrangement of colors and shapes, your brain interprets as moving. Akiyoshi Kitaoka has an extensive gallery. It comes with the warning though: ‘works of “anomalous motion illusion”, … might make sensitive observers dizzy or sick.’ (Kitaoka, 2011).

Amazing footage of an enormous flock of birds in flight by Sophie Windsor Clive.

Murmuration from Sophie Windsor Clive on Vimeo.

Brandon Kelm explains a little of how it works, mostly using terms like “scale-free correlation” and “criticality”, which pretty much sums up that we don’t know a lot about the phenomena.

NetLogo has a nice little Java model showing an attempt at simulating flocking. They give a good description of how there model works.

(via The Dish)

Most power plants create electricity by spinning a magnet while it’s inside a coil of wire. That how coal power plants do it, it’s how hydroelectric power plants do it, it’s how wind plants do it, it’s even how nuclear power plants do it; solar power panels don’t do it this way, however. The coal and nuclear plants, for example, boil water to create steam which spins the turbine that rotates the magnet.

In theory, you can use any type of power source to spin the turbine, including people power. On bicycles, you can use them to power your lights. But because you’re now using some of your mechanical energy to create electricity, it will slow you down a bit. Newer, hub dynamos, however, are apparently quite efficient.

So, in theory, you could use any type of animal to generate electricity. Including, for example, using bugs to charge your iPod.

I love how he holds up the voltmeter 34 seconds into the video to prove that his device works.

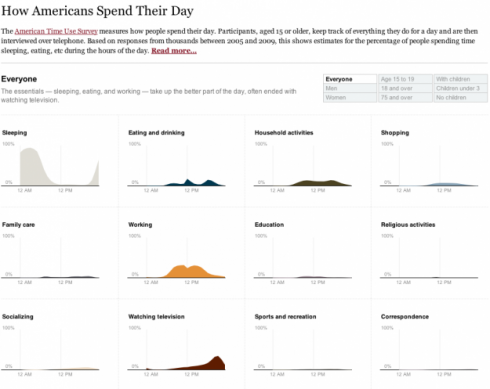

Flowing Data has an excellent set of interactive graphs showing how Americans spend their day. It’s an interesting look into modern American culture.

Main takeaway: we spend most of our time sleeping, eating, working, and watching television.

— Yau, 2011: How do Americans spend their days?

I particularly like comparing the 15-19 adolescents to adults (more time in education and less time watching television; there’s also a different sleeping pattern).

Perhaps it’s cultural conditioning, or maybe it’s genetic a predisposition, but adolescent boys to seem to have more of a predilection for war games than their female peers. The games they like tend to be first-person-shooters, like Call of Duty, and, given the trends toward improved video game graphics and remote, kinetic military action, real and simulated life seem to be converging.

Recently however, the Stuxnet virus exposed a much less glamorous picture of the future of cyber warfare. Kim Zetter has an excellent, extensive article in Wired on the computer scientists and engineers who reverse engineered the virus to try to figure out who made it and what it did. Since the virus seems to have been aimed at damaging Iran’s nuclear enrichment plants their work brought them to the edge of the world of international espionage. And they still don’t really know who created this remarkably sophisticated virus, though they suspect the U.S. and Israel.

One of the most interesting take-home messages from Zetter’s article is the amazing degree of international collaboration it took to figure things out. The virus was discovered by someone in Belarus. Researchers from the anti-virus company Symantec’s offices in California, Tokyo and Paris worked together passing information from one office to the next to keep the project going 24 hours a day. They published their findings to share them, and when they ran into stumbling blocks they couldn’t solve they put out calls for help on the internet – and people responded, bringing in expertise from Germany and the Netherlands.

The virus’ secretive creators and the open, diverse collaborators who untangled the virus reflect two conflicting aspects of the future that computer technology and the internet are making possible. And this conflict is showing up more and more in different areas – take Wikileaks for example – so it will be very interesting to see where the future takes us. Of course, we are not simply flotsam on the tides of history. As citizens of the internet, we have been enabled. We have a certain power, and a concomitant responsibility, to shape what we have for the benefit of our fellow citizens and those that come after us.

Molly Backes, an author of young adult fiction, considers the question from a mother about her teenager, “She wants to be a writer. What should we be doing?”

Her first answer was, “You really do have to write a lot. I mean, that’s mostly it. You write a lot.”

But then she thought about it, and that’s where it gets really interesting:

First of all, let her be bored. …

Let her be lonely. Let her believe that no one in the world truly understands her. …

Let her have secrets. …

…

Let her fail. Let her write pages and pages of painful poetry and terrible prose. …

Let her make mistakes.

…

Let her find her own voice, even if she has to try on the voices of a hundred others first to do so. …

Keep her safe but not too safe, comfortable but not too comfortable, happy but not too happy.

Above all else, love and support her. …

— Bakes (2011): How to Be a Writer

At the end she posts a picture of her collection of forty-two writer’s notebooks.

It’s a wonderfully written and well considered post that I’d recommend to anyone trying to teach writing and language, particularly if you take the apprentice writer approach. And, I’ve always been a great believer in the power of boredom.

Backes’ advice more-or-less summarizes my interpretation of the Montessori approach: create a safe environment and give students the opportunity to explore and learn, even if it means a certain amount of struggle and failure.

It’s also interesting to note how differently writers and other experts think, yet how much their practices overlap. Mathematician Kevin Houston also recommends writing a lot when he explains how to think like a mathematician, but his objective is to use full, rigorous sentences to clarify hard logic, and less to explore the beauty of the language or discover something profound about shared humanity.