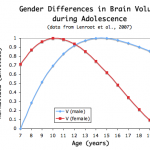

Since different student learn better in different ways, would it make sense to separate schools and classes by different learning styles? A countervailing argument, and the one upon which my Montessori middle school program (which is based on the Coe model) is predicated, is that students need to learn about different ways of learning and be able to interact with peers with different learning styles because creative endevours, especially in the future, will rely heavily on making connections between diverse fields and groups. The importance of having students interact in a diverse environment is particularly important if we can observe that students will, eventually, self-select in different fields based on their native talents, which are related to their learning styles. Students with a mathematical aptitude may tend to become engineers, more so than their peers.

So intellectual and cognitive diversity is important, yet the program also requires some uniformity. I’ve heard that, in general, students without experiences in Montessori-like environments can have a hard time adapting to the Montessori Middle School because we expect an awful lot of independence and time management that students are often not exposed to in traditional schools.

At any rate, accounting for learning-style diversity is essential, and sometimes I wonder if today, with so many more opportunities and temptations available for early specialization, if we’re not seeing further diversification in the cognitive continuum. What precisely is the point where students should begin to specialize. Matt Might model (pictured below) has specialization of education beginning at college, but it really starts earlier, at least in high school, but I wonder where the is the most appropriate initiation actually is. Historically, at least, kids were apprenticed at a very early age.