Google search a word with etymology appended and you get the etymology.

Middle and High School … from a Montessori Point of View

NPR presents the results of a Sunlight Foundation study that showed that U.S. senatorial speeches average at a 10th grade reading level. The maximum is about 16th grade (high school + 4 years of college), while the minimum is about 8th grade. The average is down one and a half grade levels from just 10 years ago.

Note that the U.S. constitution was written at an 18th grade level.

Do English speakers, whose language has a clear distinction between things that happen today and things that happen in the future, discount the value of the future in ways that the speakers of some other languages do not?

M. Keith Chen argues [pdf] that syntax plays a role. His analysis suggests that if your language’s syntax blurs the difference between today and tomorrow (as do, say, Chinese and German) then you are more likely to save money, quit smoking, exercise and otherwise prepare for times to come. On the other hand, if you have three dollars in your IRA and a big credit-card balance, it’s a safer bet you speak English or Hausa or Greek or some other language that forces speakers to distinguish present from future.

— Berreby (2012): Obese? Smoker? No Retirement Savings? Perhaps It’s Because of the Language You Speak on BigThink.

If this hypothesis holds up, there may well be significant implications for how different language speakers see and address long term environmental issues like global climate change.

(via The Dish).

Hapax legomenon –

a word which occurs only once within a context, either in the written record of an entire language, in the works of an author, or in a single text.

– definition from Wikipedia (accessed 2012)

(via The Dish via Sedivy, 2012.)

This is the first of an excellent series covering the history of English from The Open University. They make for a great spark-the-imagination lesson for etymology.

There’s lots more interesting videos at The Open University’s YouTube channel.

(via The Dish)

Middle school is where you learn the conventions of language: comma placement; who versus whom; and things like that. But language, and even its conventions, are ever evolving. Stephen Fry makes the case that we should be a little less pedantic.

I get this question occasionally from my students, and the answer is, of course, that it depends on how you define the word “sound”. Jim Baggott, on the Oxford University Press blog, goes into more detail about the roots of this philosophical conundrum, and makes the parallel to quantum physics.

Physics and philosophy are a dangerous pairing, particularly since if you know enough about one to speak intelligently about it, your probably way out of your depth in talking about the other. Just because you’re an expert in one field does not mean you’re going to be an expert in another. This is especially true of physics and philosophy, which approach the world from such different perspectives and use such different languages: to a physicist, “sound” refers to the vibrations in the air, while a philosopher might argue that “sound” only exists in our minds.

Philosophers have long argued that sound, colour, taste, smell and touch are all secondary qualities which exist only in our minds. We have no basis for our common-sense assumption that these secondary qualities reflect or represent reality as it really is. So, if we interpret the word ‘sound’ to mean a human experience rather than a physical phenomenon, then when there is nobody around there is a sense in which the falling tree makes no sound at all.

— Jim Baggott: Quantum Theory: If a tree falls in forest…

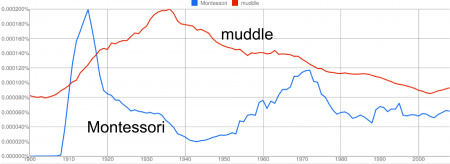

If you take all the books ever written and draw a graph showing which words were used when, you’d end up with something like Google’s Ngram. Of course I thought I’d chart “Montessori” and “muddle”.

The “Montessori” graph is interesting. It seems to show the early interest in her work, around 1912, and then an interesting increase in interest in the 1960’s and 1970’s. Like with all statistics, one should really be cautious about how you interpret this type of data, however, I suspect this graph explains a lot about the sources of modern trends in Montessori education. I’d love hear someone with more experience thinks.

Alexis Madrigal has an interesting collection of graphs, while Discover has an article with much more detail about what can be done with Google’s database.