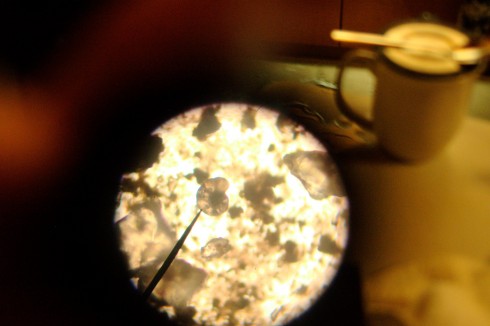

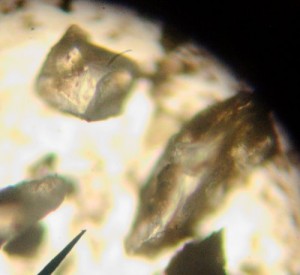

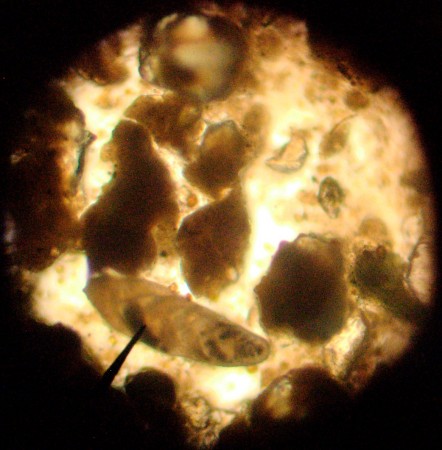

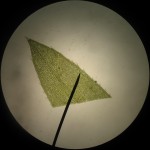

Looking at the smear slides of Coon Creek Sediment Matrix got me thinking about just how important these little, microscopic shells have been for what we know about the Earth’s past climate. In fact, they provide the background knowledge that we have about the changes in climate that we’re seeing today.

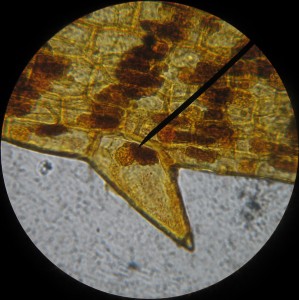

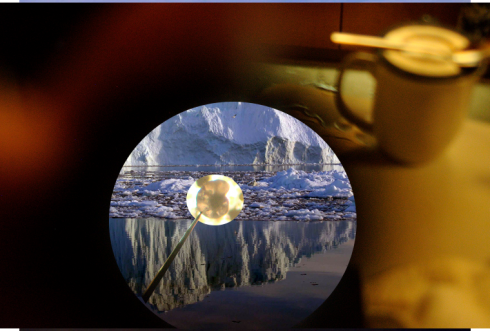

Back in the 1970’s the Deep Sea Drilling Project collected a lot of sediment cores from all around the world. The deeper you drill under the sea bed the older the sediments are, so micropaleontologists could look at how the organisms that lived in a certain area changed over time. Certain forams that could only live in warm oceans were found living far to the north. By combining all the information from all the sediment cores, they could construct paleo-geographic maps showing what the climate was like in the far past. It’s one of the reasons we know that the Jurassic climate was a lot warmer than today’s climate.

Then they invented mass spectrometers.

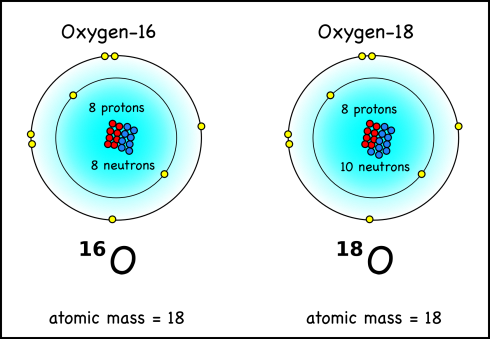

Mass specs can find the mass of individual atoms. Calcium carbonate has the chemical formula CaCO3. Water, as we should know by now, is H2O. They both have oxygen atoms, but not all oxygen atoms are equal; some are more equal. Actually, the mass of any atom is made up of the mass of the protons plus the mass of the neutrons in its nucleus. Now, by definition, any atom with eight protons is oxygen; however, while oxygen usually has eight neutrons, it sometimes has nine or even ten.

Your standard oxygen, with eight protons and eight neutrons has an atomic mass of sixteen, and is written as 16O or oxygen-16. Well, oxygen with ten neutrons is going to have a mass of eighteen (8p + 10n) and be called oxygen-18 (18O). These different versions of the same element are called isotopes.

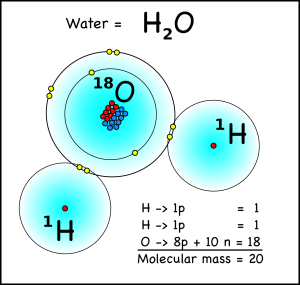

What does this have to do with climate? Well a water molecule with two hydrogen atoms, each weighing one atomic mass unit, and one oxygen-16 atom will have a molecular mass of 18, while a water molecule with an oxygen-18 atom will have a mass of 20. When water evaporates from the oceans, the water with the lighter isotope will have an easier time going from liquid to a gas in the atmosphere.

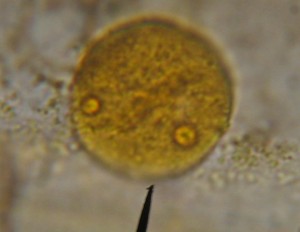

So, during an ice-age for instance, lots of water evaporates from the oceans, falls on land as snow, and then gets trapped in the enormous glaciers that cover entire continents. Since the lighter water molecules evaporate easier from the oceans, they’re the ones that will end up falling as snow and being compressed into glacial ice. The water molecules left behind in the ocean will tend to have the heavier oxygen-18 isotopes. Since the forams use the ocean water as part of the process of creating their calcium carbonate shells, the oxygen from the water ends up in the carbonate (CO3) of the shells. Since the ocean water has extra oxygen-18s during an ice-age, then the shells will have extra oxygen-18 isotopes during an ice-age.

Therefore, by measuring the amount of heavy oxygen-18 isotopes that are in a single shell, we can tell how large the glaciers were at the time that shell formed, and tell what the global climate was like.

Of course there are some interesting complexities to the story, but that’s the general idea of how the microscopic shells of long-dead plankton can tell us about the history of the Earth’s climate.