This little guy seemed to like hanging out on the bench near the back door. I believe it’s a Great Spangled Fritillary (Speyeria cybele).

Middle and High School … from a Montessori Point of View

This little guy seemed to like hanging out on the bench near the back door. I believe it’s a Great Spangled Fritillary (Speyeria cybele).

When you look at the sunlight reflected off this black insect’s wings at just the right angle, they blaze bright blue. The phenomena is called iridescence, and results from the way different wavelengths of light refract through the wing membrane. Blue light is of just the right wavelength that the light reflected off the top of the membrane and the light that’s refracted through the membrane constructively interfere. The Natural Photonics program at the University of Exeter has an excellent page detailing the physics of iridescence in butterflies (Lepidoptera), and the history of the study of the subject.

Down at the creek the water striders are out. They can stand, walk and jump on the surface of the water without penetrating the surface because of the force of surface tension that causes water molecules to stick together — it’s the same cohesive force that make water droplets stick to your skin. I got a decent set of photos to illustrate surface tension.

The green canopy that over hangs the creek allows for some nice photographs.

One of my favorite things about the Fulton School campus is the little creek that runs along the boundary. It’s small, dynamic, and teeming with life.

The crayfish are out in force at the moment. Some of the high-schoolers collected one last fall and it survived the winter in our fish tank (also populated with fish from the creek).

They are quite fascinating to observe; wandering around the sandy bed as if they own the place; aggressive with their pincers occasionally; but then darting backward amazingly fast if they feel threatened.

The one in our tank has just molted a second time, so now we have two almost perfect exoskeletons sitting around the science lab.

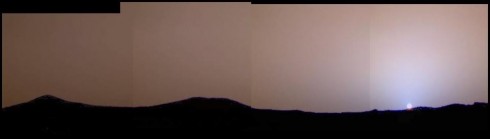

The dust in Mars’ atmosphere scatters red, while the major gasses in Earth’s atmosphere (Nitrogen and Oxygen) scatter blue light. Longer wavelengths of light, like red, will bounce off (scatter) larger particles like dust, while shorter wavelengths, like blue light, will bounce of smaller particles, like the molecules of gas in the atmosphere. The phenomena is called Rayleigh scattering, and is different from the mechanism where different molecules absorb different wavelengths of light.

Ezra Block and Robert Krulwich go into details on NPR.

In addition to eating the bulbs of the radishes, the leaves are also edible. I heartily endorse Clotilde Dusoulier’s Radish Leaf Pesto. The slight spiciness of the leaves gives it a delightful frisson.

Pesto recipes are pretty flexible. I added some fresh cilantro from the garden, some frozen basil leaves, used ground almonds for the nut component, a bit of Manchego for the cheese, and doubled the garlic. I also added a little white wine to reduce the viscosity. I quite liked the end result — we had it on pasta — even if some others though it was a little too adventurous.

I took a half-day trip during spring break (somewhere around the 31st) to the Shaw Nature Reserve in Gray Summit. I was hoping to find some books on native, Missouri, flora and fauna, and see if the Reserve would be a good place for a field trip (they have sleeping facilities so even overnight trips are a possibility).

I found a number of books, including a nice one on mushrooms, and while I could have, I did not pick up one on wildflowers (of which there were several). Of course, spring is the perfect time to see wildflowers, especially since we ended up hiking the Wildflower Trail, so I’m probably going to have to go back sometime soon.

The lady at the main office (where you pay $5/adult) recommended we take the Wildflower Trail and then cut down south to the sandbar on the Meramec River, which is an excellent place for skipping rocks. She also recommended I take my two kids to their outdoor “classroom” for some real, unstructured play.

View Shaw Nature Reserve – Wildflower Trail in a larger map

Without a reference book, I’ve had to resort to the web for identifications, with only a little success, so I’ll post a few of my photographs here and update as I identify them.

The following two pictures are of a flower that was found covering the hillslope meadows; open areas with short grass.

Like little stars in the daylight, these small, white flowers meadow flowers almost sparkle.

Pretty, small, yellow, meadow flowers.

These bent-over flowers can be found on the lower, shadier edges of the hillslope meadows.

Iris’ were also in bloom.

Another herbaceous, yellow flower.

More, tiny, delicate flowers.

Once you get under the canopy, you run into some broader leaved plants and their own, interesting flowers.

We ended up spending a lot of time on the sandbar, learning to skip rocks and hunting for clams, but I save that for another post. And we never did get to the play area; that’ll have to wait for the next trip.

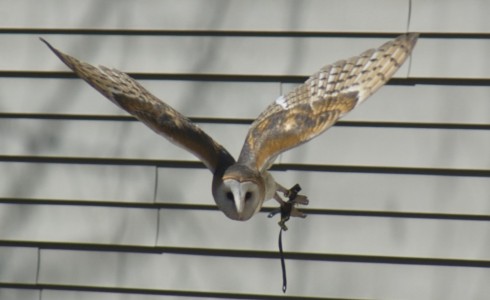

A discussion of the physics of flight, interspersed with birds of prey swooping just centimeters from the tops of your head, made for a captivating presentation on avian aerodynamics by the people at the World Bird Sanctuary that’s just west of St. Louis.

The presentation started with the forces involved in flight (thrust, lift, drag and gravity). In particular, they focused on lift, talking about the shape of the wings and how airfoils work: the air moves faster over the top of the wind, reducing the air pressure at the top, generating lift.

Then we had a demonstration of wings in flight.

We met a kestrel, one of the fastest birds, and one of the few birds of prey that can hover.

Next was a barn owl. They’re getting pretty rare in the mid-continent because we’re losing all the barns.

Interestingly, barn owls’ excellent night vision comes from very good optics of their eyes, but does not extend into the infrared wavelenghts.

Finally, we met a vulture, and learned: why they have no feathers on their heads (internal organs, like hearts and livers, are tasty); about their ability to projectile vomit (for defense); and their use of thermal convection for flying.

The Sanctuary does a great presentation, that really worth the visit.