Superbugs. When the environment changes, those fortunate organisms who are better adapted to the new environment will live longer and produce more offspring than those that are poorly adapted. (The Chrysalids, is a great book that encapsulates this principle in a powerful coming-of-age story.)

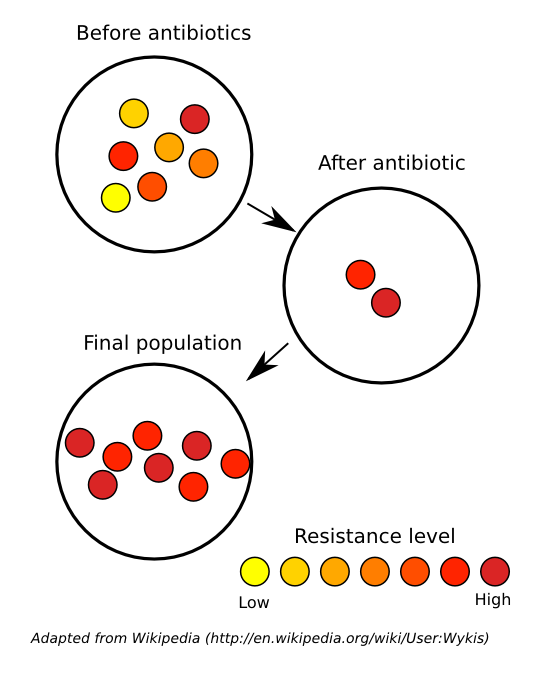

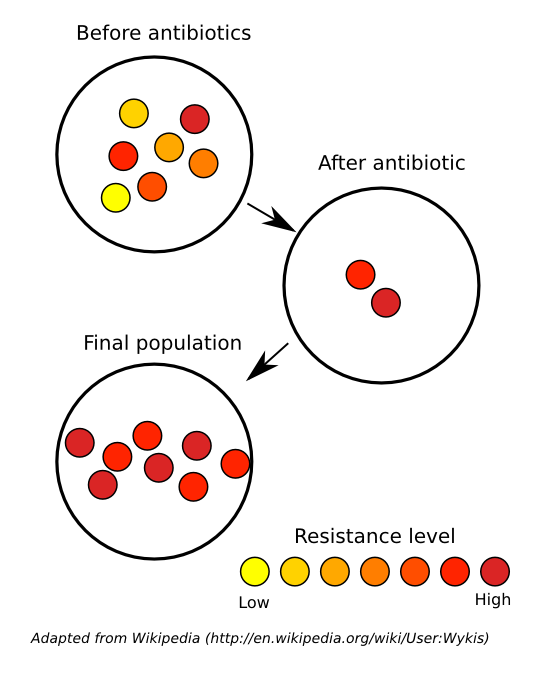

When it comes to bacteria, some small fraction of any strain of bacteria infecting you are, because of random genetic mixing, more resistant to the antibiotics you may be taking. This is why your doctor often makes you to take the antibiotic for a few days after the symptoms are gone; to kill those last most resistant bacteria cells.

Unfortunately, not everyone takes the full course of antibiotics, and some bacteria cells are extremely drug resistant. Over the years since the discovery of penicillin about a century ago, bacterial cells resistant to penicillin have been surviving and reproducing, so that there are now strains of bacteria that are resistant to the drug.

Fortunately drug researchers are developing new antibiotics all the time. When your doctor prescribes one antibiotic and it doesn’t work, they can usually prescribe another that will work because a bacteria strain that has an immunity to one drug might not have an immunity to another, especially if the other is a very different type of drug.

Unfortunately, some bacterial strains have developed that are resistant to a lot of different types of drugs (according to the World Health Organization), and these bacteria are responsible for thousands of deaths in hospitals around the world each year.

Norway has come up with one promising solution; don’t use as many antibiotics. Instead of treating every, or even most colds with antibiotics, their doctors take a wait and see attitude. They prescribe other medicines that reduce the symptoms, the coughing and runny nose, and let the body’s immune system deal with the bacterial infection. And it is working. In Norway, they are able to use penicillin varieties that would not be effective in other countries.

Without the overuse of antibiotics, drug-resistant strains of bacteria are not as competitive as other strains that commonly infect people. Without antibiotic overuse the superbugs aren’t so super after all. So, using less antibiotics means fewer infections with drug-resistant strains.

It’s a bit as if, somewhere in the forests of India, one tiger was born that was much, much better at hiding from and attacking people than the ordinary tiger, but it was smaller than other tigers. Ordinarily, this “supertiger” and its genes would probably die out because it would not be able to compete with the other tigers to reproduce. However, when people start hunting tigers, the supertiger survives better and passes on its genes. Now we have alot more supertigers and a lot more people are being attacked. All because people started killing the tigers.

Evolution is a fascinating process with such a multitude of complicated interactions. I also recommend that students read the introduction to the Origin of Species. It is truly an example of beautiful science. The language is challenging but, I think, worth it.