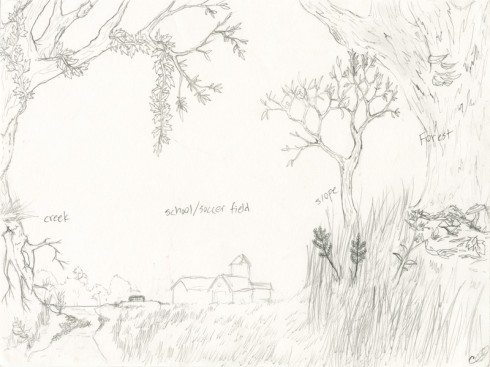

With the help of Scott Woodbury from the Shaw Nature Reserve, Dr. Sansone lead the effort to remove the six mature Bradford Pear trees from the front of the school over the last interim. We collected slices of each of the trees so students could do a little dendrological work with the tree rings.

The trees were planted as part of the original landscaping of the school campus. They’re pretty in the spring and fall, but are an aggressive invasive species.

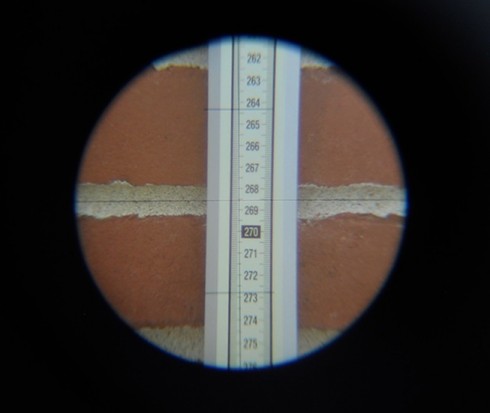

The fast growth, however, make for wide growth rings. In fact, in addition to the annual rings, there are several millimeter wide sub rings that are probably related to specific weather events within the year. I’d like to see if we can co-relate some of the sub-ring data to the longer term instrumental record of the area.

The tree cutting was quite fun as well, despite being done on a cold day near the end of November. Students helped stack logs and organize branches along the road for the woodchipper. I learned how to use a chainsaw.