This little guy seemed to like hanging out on the bench near the back door. I believe it’s a Great Spangled Fritillary (Speyeria cybele).

Middle and High School … from a Montessori Point of View

This little guy seemed to like hanging out on the bench near the back door. I believe it’s a Great Spangled Fritillary (Speyeria cybele).

If … you had asked, “Should I become a professional writer?” the answer would have been No. And why not? The answer would have been that if you were destined to become a professional writer, you wouldn’t have asked the question; you would have known the answer for yourself and to hell with what anybody told you.

— Malcolm Cowley in a letter to Richard Max ᔥ Rebecca Davis O’Brien (2012): Malcolm Cowley, Life Coach, in the Paris Review of Books.

Advice from a writer to a potential writer. A career in writing is a difficult choice: “the rewards come late”; “most writers are failures”. You need to want to write. Intrinsic motivation.

ᔥ Rebecca Davis O’Brien (2012): Malcolm Cowley, Life Coach ↬ The Dish.

A ball rolling down a ramp hits a car which moves off uphill. Can you come up with an experiment to predict how far the car will move if the ball is released from any height? What if different masses of balls are used?

For my middle school class, who’ve been dealing with linear relationships all year, they could do this easily if the distance the car moves is directly proportional to height from which the ball was released?

The question ultimately comes down to momentum, but I really didn’t know if the experiment would work out to be a nice linear relationship. If you do the math, you’ll find that release height and the maximum distance the car moves are directly proportional if the momentum transferred to the car by the ball is also directly proportional to the velocity at impact. Given that wooden ball and hard plastic car would probably have a very elastic collision I figured there would be a good chance that this would be the case and the experiment would work.

It worked did well enough. Not perfectly, but well enough.

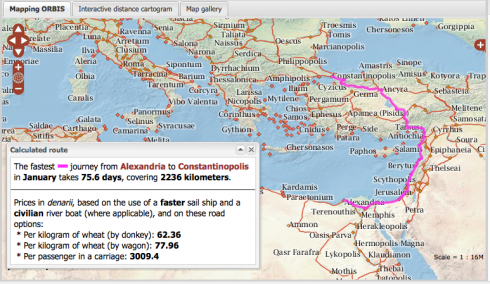

Say I wanted to get from Alexandria, Egypt, to Constantinople, I don’t trust boats, and it’s 1800 years ago. Well, instead of mapping it with Google I’d have to use ORBIS instead. ORBIS tells me that it would take two and a half months and cost me 3000 denarii (about $30,000).

Which seems like a bit much. But, since I absolutely have to get to the capital, I think I’ll price out a coastal boat route. That reduces the price by 80%, and the time to three weeks.

If I was really cheap, and was willing to risk the open Mediterranean, the time could be chopped down to less than two weeks, at a cost of only 374 denarii.

In ORBIS, Walter Scheidel and Elijah Meeks have created a fascinating resource for the study of the geography and history of Roman civilization.

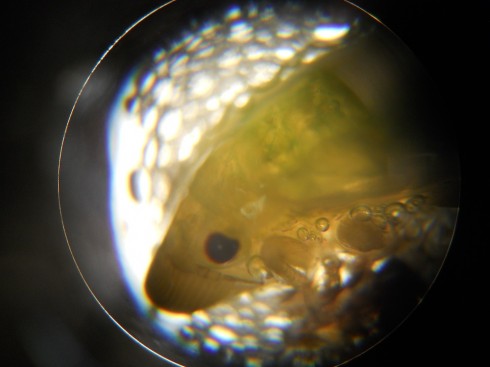

On the wildgrass-covered slope next to school, you can see a lot of these little foamy things, that look like spit, on the stalks of the tall grasses and herbs.

One of my students collected some to look at under the microscope. We thought it might be the collection of eggs of some creature. It turned out that, at the center of the foam, was what looked like an immature insect. A quick google search for “spit bugs” turned up froghoppers, whose nymphs create the spit to protect them from the environment (heat, cold) and hide themselves from predators.

They suck the sap of the plants they’re on, and can be agricultural pests.

Note to self: The Tavern Rock Cave, where Meriwether Lewis almost fell to his death, is 45 minutes from the St. Albans Lake (walking at a fair pace mind you), not “just 20”, no matter what the students claim.

It’s a little tricky to get to, and we couldn’t spend more than a few minutes there because of the longer than expected walk, but it’s a nice place to visit because of the history and beautiful geology (jointed limestone and dolomite outcrops; scree slopes at the angle of repose; Ordovician fossil imprints).

P.S. The National Park Service has an excellent site on the Lewis and Clark Expedition that includes maps, their itinerary, and a long list of sites they visited.

When you look at the sunlight reflected off this black insect’s wings at just the right angle, they blaze bright blue. The phenomena is called iridescence, and results from the way different wavelengths of light refract through the wing membrane. Blue light is of just the right wavelength that the light reflected off the top of the membrane and the light that’s refracted through the membrane constructively interfere. The Natural Photonics program at the University of Exeter has an excellent page detailing the physics of iridescence in butterflies (Lepidoptera), and the history of the study of the subject.