I sent a couple of my algebra students down to the pre-Kindergarten classroom to burrow one of their Montessori works. They were having a little trouble adding polynomials, and the use of manipulatives really helped.

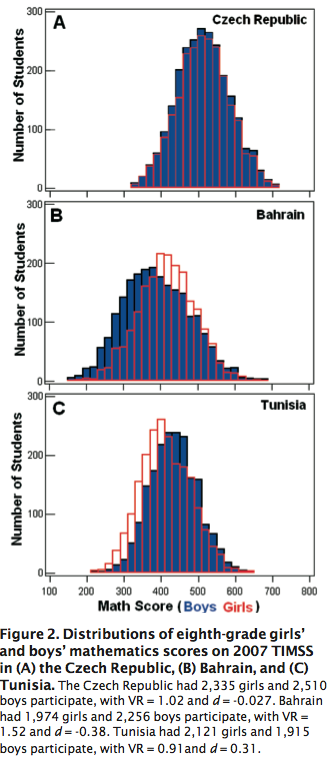

The basic idea is that when you add something like:

![]()

you can’t add a n3 term to a n2 or a n term. You only combine the terms with the same degree (and same variables). So the equation above becomes:

![]()

which simplifies to:

![]()

The kids actually enjoyed the chance to run downstairs to burrow the materials from their old pre-K teacher (and weren’t they quite good about returning the materials when they were done with them).

And it clarifies a lot of misconceptions when you can clearly see that that you just can’t add a thousand cube to a ten bar — it just doesn’t work.