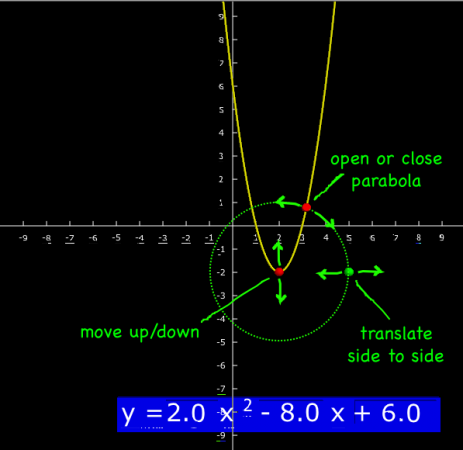

So I put together this interactive parabola program using VPython (code here) for students encountering these curves in Algebra.

It’s a more interactive version of the Excel parabola program in that you can move the curve by dragging on some control points, rather than just having to enter the coefficients of the equation. The program is still in development, but it is at a useful stage right now, so I thought I’d make it available for anyone who wanted to try it.

The program is fairly straightforward to use. You can move the curve (translate it) up and down, and expand or tighten the area within the parabola.

The program also displays the equation of the curve in standard form:

![]()

.

Next Steps

I’m also working making the standard equation editable by clicking on it and typing, and am considering showing the x-axis intercepts, which will give algebra students a nice, visual way to of checking their factoring.

References

Coffman, J., 2011 (accessed). Translating Parabolas. http://www.jcoffman.com/Algebra2/ch5_3.htm

Math Warehouse, 2011 (accessed). Equation of a Parabola

Standard Form and Vertex Form Equations, http://www.mathwarehouse.com/geometry/parabola/standard-and-vertex-form.php#

WolframAlpha.com, 2011 (accessed). http://www.wolframalpha.com/input/?i=a^2+x^4%2Bx^2-r^2%3D0