How to create ultra-cold temperatures (and what it tells us about the universe).

And this article (Below Absolute Zero: Negative Temperatures Explained) tells how to get below absolute zero.

Middle and High School … from a Montessori Point of View

How to create ultra-cold temperatures (and what it tells us about the universe).

And this article (Below Absolute Zero: Negative Temperatures Explained) tells how to get below absolute zero.

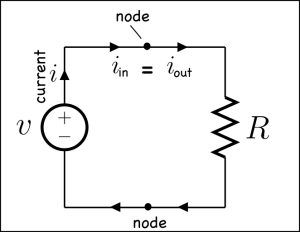

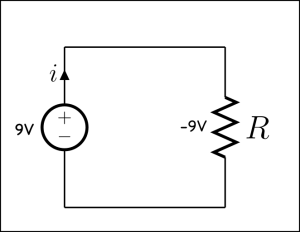

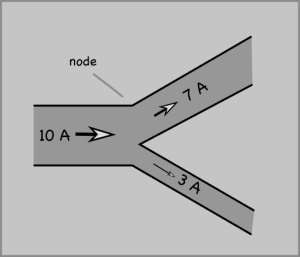

Studying voltage and current in circuits can start with two laws of conservation.

Note: Some of the links are dead, but this MIT Opencourse pdf has a detailed explanation. And Kahn Academy has some videos on the current laws as well.

Things get more interesting when we get away from simple circuits.

Note that the convention for drawing diagrams is that the current move from positive (+) to negative (-) terminals in a battery. This is opposite the actual flow of electrons in a typical wired circuit because the current is a measure of the movement of negatively charged electrons, but is used for historical reasons.

Based on the MIT OpenCourseWare Introduction to Electrical Engineering and Computer Science I Circuits 6.01SC Introduction to Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Spring 2011.

Physicists in Europe Find Tantalizing Hints of a Mysterious New Particle: This new particle, if confirmed to exist (the data is not conclusive) seems to go beyond the Standard Model of physics that we know and love.

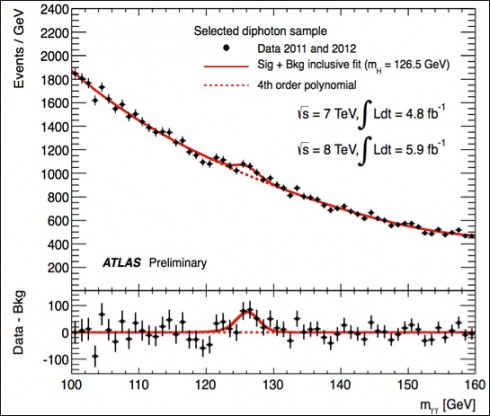

The last sub-atomic particle discovered was the Higgs boson, which is shown in the graph below.

For the student who asked how do we know about black holes if we can’t see them. From NASA. Based on the paper: http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/chandra/destroyed-star-rains-onto-black-hole-winds-blow-it-back.html

I need some students to try this at school. Muscle fibers that contract on heating sounds like a great way to open and close vents for air circulation (in the chicken coop to start with).

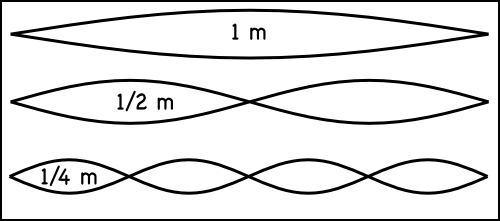

Pluck a string on a guitar and the sound you hear depends on how fast it vibrates. The frequency is how many times it vibrates back and forth in each second. An A4 note has a frequency of 440 vibrations per second (one vibration per second is one Hertz).

The vibration frequency of a guitar string depends on three things:

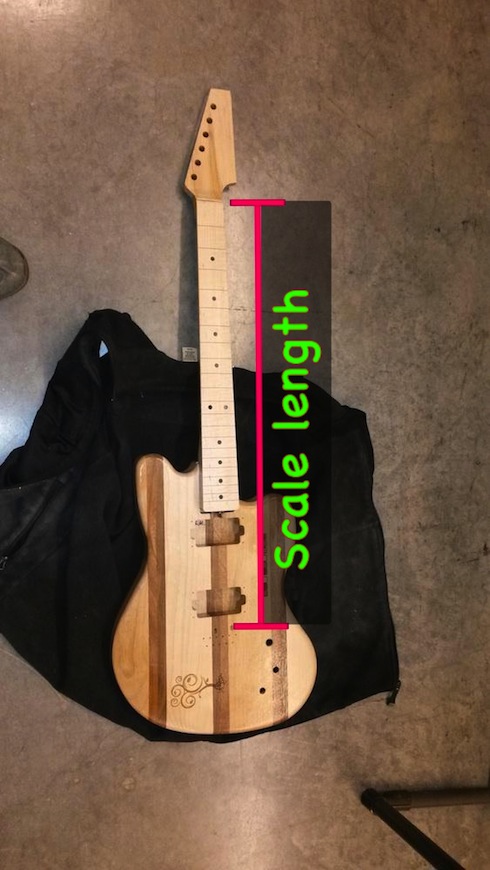

Guitar string sets come with wires of different masses. The guitar has little knobs on the end for adjusting the tension. For building the guitar, you have the most control over the last last parameter, the length of the string, which is called the scale length. Since the guitar string masses are pretty much set, and the strings can only hold so much tension, there are limits to the scale length you can choose for your guitar.

In a guitar, the scale length only refers to the length of the string that’s actually vibrating when you pluck the string, so it’s the distance between the nut and the bridge. For many guitars this turns out to be about 24.75 inches.

To play different notes, you shorten the vibrating length of the string by using your finger to hold down the string somewhere along the neck of the instrument. The fret board (which is attached to the neck) has a set of marks to help locate the fingering for the different notes. How do you determine where the fret marks are located?

Well, the music of math post showed how the frequency of different notes are related by a common ratio (r). With:

![]()

So given the notes:

| Note Number (n) | Note |

|---|---|

| 0 | C |

| 1 | C# |

| 2 | D |

| 3 | D# |

| 4 | E |

| 5 | F |

| 6 | F# |

| 7 | G |

| 8 | G# |

| 9 | A |

| 10 | A# |

| 11 | B |

| 12 | C |

Since the equation for the frequency of a note is:

![]()

we can find the length the string needs to be to play each note if we know the relationship between the frequency of the string (f) and the length of the string (l).

It turns out that the length is inversely proportional to the frequency.

![]()

So we can calculate the length of string for each note (ln) as a fraction of the scale length (Ls).

![]()

substituting for fn gives:

![]()

but since we know the length for f0 is the scale length (Ls) (that inverse relationship again):

![]()

giving:

When we play the different notes on the guitar, we move our fingers along the neck to shorten the vibrating parts of the string, so the base of the string stays at the same place–at the bridge. So, to mark where we need to place our fingers for each note, we put in marks at the right distance from the bridge. These marks are called frets, and we’ll call the distance from the bridge to each mark the fret distance (D_n). So we reformulate our formula to subtract the length of the vibrating string from the scale length of the guitar:

The fret marks are cut into a fret board that was supplied by the guitarbuilding team, which we glued onto the necks of our guitars. We did, however, have to add our own fret wire.

The team also has an activity for students to use a formula (a different one that’s recursive) to calculate the fret distance, but the Excel spreadsheet fret-spacing.xls can be used for reference (though it’s a good exercise for students to make their own).

Mark French has an excellent YouTube channel on Mechanical Engineering, including the above video on Math and Music. The video describes the mathematical relationships between musical notes.

Given the sequence of notes: C, C#, D, D#, E, F, F#, G, G#, A, A#, B, C.

Let the frequency of the C note be f0, the frequency of C# be f1 etc.

The ratio of any two successive frequencies is constant (r). For example:

![]()

so:

![]()

We can find the ratio of the first and third notes by combining the first two ratios. First solve for f1 in the first equation:

![]()

solving for f1,

![]()

now take the second ratio:

![]()

and substitute for f1,

![]()

which gives:

![]()

We can now generalize to get the formula:

or

where,

- n – is the number of the note

From this we can see that comparing the ratio of the first and last notes (f12/f0) is:

![]()

Now, as we’ve seen before, when we talked about octaves, the frequency of the same note in two different octaves is a factor of two times the lower octave note.

So, the frequency ratio between the first C (f0) and the second C (f12) is 2:

![]()

therefore:

![]()

so we can now find r:

![]()

![]()

Finally, we can now find the frequency of all the notes if we know that the international standard for the note A4 is 440 Hz.

Mark French has details on the math in his two books: Engineering the Guitar which is algebra based, and Technology of the Guitar, which is calculus based.