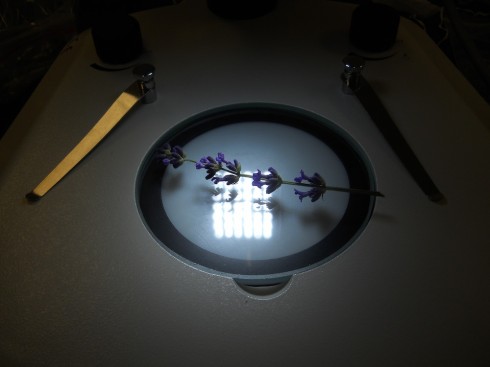

This year, the creek is teeming with crayfish, especially compared to last year during the drought when the creek dried up and the crustaceans were hard to find. I had five students out collecting organisms on Wednesday, and they came back with ten crayfish ranging in size from a couple centimeters long, to one that was about 12 centimeters from claws to tail.

I was just looking at one of the pictures I took and realized that I did not know what species it belonged to. I’ll be having students do reports on individual species for biology next year, and I’d be very surprised if someone did not choose crayfish. They’re so many of them and, as my students from Wednesday will attest, they’re just so charismatic. While I’ve not looked into it much myself, the Crayfish & Lobster Taxonomy Browser seems a decent place to start researching.